Dear readers, it feels strange entering your inbox on a weekday, almost like an an intrusion of sorts, akin to when people drop by unannounced, just because they can. Always grinds my gears! But I assure you my intentions are less devious.

I wanted to share a bit of insight into what I’m currently reading. I’m not the biggest fan of lists or as they say ‘listicles’, but as we approach the festive period, I thought I’d offer a (mini) curation of books I’ve recently read that have resonated with me both emotionally and philosophically. Think of this not as a hierarchically arranged list but as a menu of literary delights that speak to your soul in a language that defies all logic.

(1) Diaries - 1910-1923 by Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) needs no introduction. The German-speaking Bohemian novelist and short-story writer remains an influential figure in the hearts and minds of most literary aficionados.

These diaries authored by Kafka cover the years 1910 to 1923 and provide piercing insight into life in Prague including Kafka’s accounts of his vivid dreams, the valorisation of his father, and the woman he could not bring himself to marry. His death from a lifelong struggle with tuberculosis, a year after this was written, contextualises much of this work as an unflinching look at human mortality.

Kafka had an uncanny philosophical aptitude for capturing despair in all its haunting beauty, masterfully articulated with his prodigious gift for metaphors. From his sense of guilt to his feelings of being an outcast, there is an embedded meta-image of intensity and poetic romance in every delicately chosen word and phrase - a feature that is surprisingly not lost in the translated version of the book. Who would have thought that words could carry such lush and extravagant despair.

Kafka is the type of writer that makes you think if his struggles with mental depression had a role to play in making him the literary genius that he was. While we are invited to bath in the vast sea of anguish surrounding his life, we are also reminded of Kafka’s sublime ability to stand and watch it from the shore as the waves of troubles and sorrows wash over him. Ultimately, the book asks if his compulsive search for new means of describing his inner life became an end in itself.

“Being alone has a power over me that never fails. My interior dissolves (for the time being only superficially) and is ready to release what lies deeper. When I am willfully alone, a slight ordering of my interior begins to take place and I need nothing more.”

― Franz Kafka, Diaries, 1910-1923

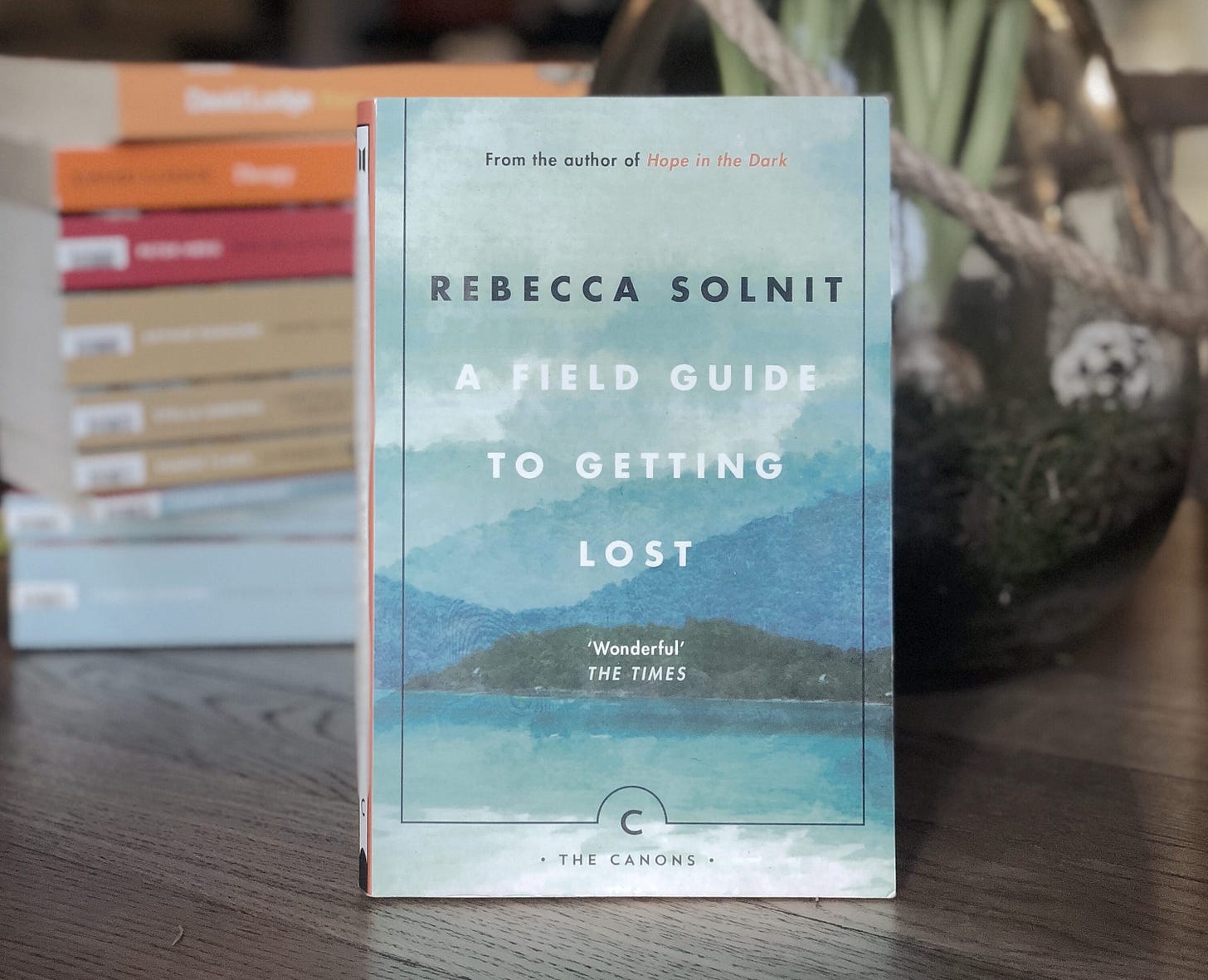

(2) A Field Guide to Getting Lost by Rebecca Solnit

Rebecca Solnit impeccably and intimately captures the voyage of discovery - that liminal moment when one is lost only to be re-born again on the other side, traversing across different identities and modes of consciousness, always on the move but never arriving. Solnit provides a thorough exploration into issues of wandering and the utility of the unknown.

The essays in this compilation read as mosaics of cultural history, autobiography, nature writing: all of which reward careful reading. Solnit’s meanderings and digressions are disorienting and dislocated at times, but give in to this psychedelic journey through the labyrinth of narratives, and you will be rewarded with an enthralling understanding of why ‘getting lost’ is part of a broader evolutionary journey. The book as a whole captures the thrill of improvisation and succumbing to the unknown; it compels us to acknowledge that feeling empty is sometimes the only means towards fulfilment.

“Lost really has two disparate meanings. Losing things is about the familiar falling away, getting lost is about the unfamiliar appearing. There are objects and people that disappear from your sight or knowledge or possession; you lose a bracelet, a friend, the key. You still know where you are. Everything is familiar except that there is one item less, one missing element. Or you get lost, in which case the world has become larger than your knowledge of it. Either way, there is a loss of control. Imagine yourself streaming through time shedding gloves, umbrellas, wrenches, books, friends, homes, names. This is what the view looks like if you take a rear-facing seat on the train. Looking forward you constantly acquire moments of arrival, moments of realization, moments of discovery. The wind blows your hair back and you are greeted by what you have never seen before. The material falls away in onrushing experience. It peels off like skin from a molting snake. Of course to forget the past is to lose the sense of loss that is also memory of an absent richness and a set of clues to navigate the present by; the art is not one of forgetting but letting go. And when everything else is gone, you can be rich in loss.”

― Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost

(3) The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales, Oliver Sacks

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales is a 1985 book by neurologist and essayist Oliver Sacks describing the case histories of some of his patients. The creatively penned title is derived from one of Sacks’ patients, Dr P, who has visual agnosia, a neurological condition that leaves him unable to recognise familiar faces and objects. Right from the first few pages, Sacks’ characteristic quirk, candour, and exuberant creative curiosity shines through.

This is not only an informative work on neurological disorders, but a humbling meditation on the mystical beauty of imperfection. It provides a painstakingly detailed introduction into the brain's remarkable ability to overcompensate for cognitive deficiencies.

As a result of these heightened states of perception, the infinitely complex worlds of each individual are realised through the way they organise and engage with the ordinary, through the specialist prisms of mathematics, dance, music, or the visual arts. Sacks contends that those with cognitive impairments often remarkably transcend the boundaries of what a ‘normal functioning’ person could be expected to achieve. Their minds are naturally configured to adapt and identify specific detail that is often missed by the rest of us.

There is a level of empathy in Sacks writing about the challenges and stigma associated with having a neurological disorder, but instead of embarking on a never-ending rhetoric of despair, he swashes his patients (‘cases’) with exuberant colour. Rather than adopting the tone of a dry psychological manual or pompous cigar smoking intellectual, Sacks presents each case as a heart-warming appraisal of human character and resilience.

The above list wasn’t based on an alchemy of various readership statistics and other sophisticated data voodoo. It is a wholly subjective selection of books intended to provide you with ample respite from, what is for many, an emotionally topsy-turvy and chaotic time of year. If you want a broader list of recommendations, feel free to drop me a line below.

Take care,

Josh

I actually don't enjoy Solnit all that much in general, but that particular one and "The Faraway Nearby" I really, really liked.