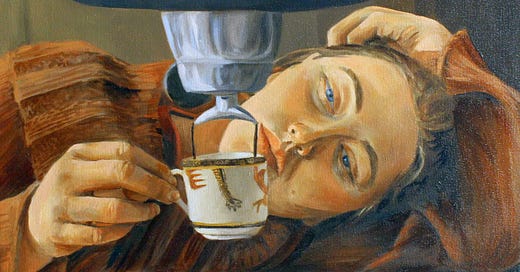

Wait! Just Listen is a free weekly Sunday newsletter chronicling all matters relating to the human condition, best read in the morning with a freshly brewed cup of coffee and a side of raspberry jam biscuits. As Virginia Woolf once said, “pleasure has no relish unless we share it”, so if you enjoy my written musings please subscribe and share this with friends and family.

A good cup of coffee has a certain tang in how it fills the throat on the way down. It delivers a flavour that is deceptively subtle at first but one that gradually acquaints itself with your taste buds with assuring ease, lingering as a gustatory memory. And if you are a coffee aficionado (snob) like me, you’d know that coffee has a fragrance that promises more than the taste delivers. While its salubriousness is at times contested, its global popularity cannot be discounted.

The common man’s drink has been credited for inspiring Nobel-Prize wins, revolutions, and musical masterpieces. But beneath this romanticised vision of exuberance lies the brutally harsh reality of tedious and economically exploitative work on an incredibly labour-intensive and agriculturally sensitive crop. The simple truth is that growing and harvesting coffee is luckless and backbreaking work. Frugality, austerity, and repetition are a staple part of an average day in the life of a coffee harvester. American anthropologist, Sidney Mintz, once noted; what sweetened the cup of Europeans was bitter to the people who produced it.

Millions of words have been written about coffee’s roots to slavery and how it was then pushed on a pliant proletariat by big business. The following vignette from Mark Pendergrast’s book, ‘Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World’ is one such account. It is emblematic of coffee’s embedded paradoxes specifically in the fields of Guatemala:

Tiny women carry amazingly large bags, twice their eighty-pound weight. Some of the women carry babies in slings around front. A good adult picker can harvest over two hundred pounds of cherries and earn $8 a day, more than twice the Guatemalan minimum daily wage.

In Guatemala, the contrast between poverty and wealth is stark. Land distribution is lopsided, and those who perform the most difficult labour do not reap the profits. Yet there is no quick fix to the inequities built into the economic system, nor any viable alternatives to coffee as a crop on these mountainsides…

As the workers bring in the harvest, I ponder the irony that, once processed, these beans will travel thousands of miles to give pleasure to people who enjoy a lifestyle beyond the imagination of these Guatemalan laborers. Yet it would be unfair to label one group “villains” and another “victims” in this drama. I realize that nothing about this story is going to be simple.

These harrowing tales of struggle and contrasting fates have seen the light of the day thanks to the probing pen of writers like Pendergrast. Every coffee bean tells a story of determination and rugged perseverance. Of modern-day slavery. Of false-dawns. Of resignation. Of acceptance. Of both pain and pleasure. But it also tells us how the storytelling can provide a poignant and piercing appraisal of social reality and systemic failure. It falls upon the shoulders of the writer to carefully and respectfully peel away layers of narrative detail.

Whilst I’ll be first to admit that Pandergrast is no Proust when weaving a tale, his book conveys a meaningful convergence of two very different slice-of-life predicaments - that of the harvester and the coffee drinker. It is a story that could so easily be forgotten or relegated as an inevitable feature of capitalism at work, an endnote or ‘blemish’ in the history of mass consumption, where mixed fortunes are seen as a staple by-product rather than an exception.

But therein lies the beauty of writing and its ability to animate and breath life into these pressing social undercurrents. It casts a clarifying light on society’s less thought about fissures, showcasing the implicit moral values at stake in seemingly innocuous daily rituals, like having a cup of coffee.

Writers have an obligation to identify moments of conflict and contradiction and they similarly have the creative licence (if they so wish) to prefigure a reality that is somewhat more desirable and attuned with compassion and equity.

For me, coffee is an interesting product of our times not only because of its cultural significance, but also in how it simultaneously serves as a zeitgeist of both ‘high culture’ and ‘art’, and that of gruelling poverty and human exploitation. To tell the story of coffee from the vantage point of one and not the other betrays the accountability and truth standard that every writer should aspire towards.

In that respect, the production and cultural uptake of coffee provides the perfect scene for understanding the virtues behind great storytelling. Penetrative storytelling often deals in the illumination of complexity; it provides new angles to how we see the opaque parts of some of our most quotidian rituals.

It is also important to know that stories don’t simply capture reality. They allow us to vicariously live through various snippets of existence, offering a dose of the limitations, sufferings, possibilities and hopes faced by humanity.

Ultimately, the stories that move us often remind us of something much forgotten; that most pleasures rely on someone else’s pain, or the possibility of it. Coffee is no different.