Welcome to Wait! Just Listen, a weekly series of short essays dedicated to the art of unpacking moments of humanness from the all-consuming web of digitisation. If this type of content tickles your fancy or any other part of your intellectual self, please consider subscribing.

The late French novelist, Georges Perec wrote La Disparition (1969) without ever using the letter “e”. His subsequent novella Les Revenentes (1972) only featured the vowel “e”, leaving out the other 5. Lipograms such as Perec’s intentionally rebel against artistic convention. But for Perec, it was more than a literary sleight-of-hand. It was a way of confronting the painful reality of loss.

Perec was born the only son of Polish-Jewish parents who both died in the second world war: his father fighting for the French army, and his mother at Auschwitz. When the Nazis stormed into the town where he had taken refuge with relatives, the name Perec, being of Breton heritage, did not attract undue attention from the Nazis. His survival as a child was remarkably linked to this fortunate instance of wordplay. Naturally, his predisposition to linguistic coincidences meant that compositional structure served as his refuge - a way of coping with what he didn’t have. An opportunity to confront his discomfort and fate.

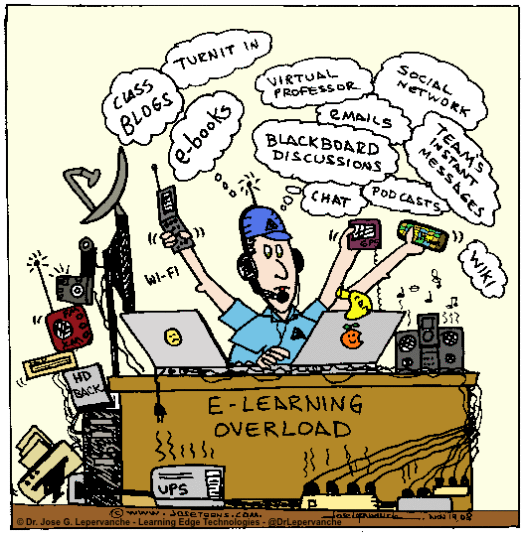

Perec’s literary experimentation has made me question how restraint lends itself to our hyper-digitised world. There couldn’t be an environment more dissimilar to the realities faced by Perec than the one we inhibit now - a world of extreme digitisation, information overload and perennial connectivity. It may be a farcical contrast but that is exactly why it is a contrast that is necessary. Not just to see how much we’ve accumulated but, perhaps rather paradoxically, how much we’ve lost.

Let’s get the semantics out of the way first. I see ‘restraint’ as the kinder cousin to ‘constraint’. Restraint is an effort at purposeful reduction; as a way of taming and economising, to say more with less. Restraint is a calculation towards constraint but with a few strategic allowances. Think of it as white spaces in a billboard advertisement or pauses in a conversation. They are all moments that inform communication through the very virtue of doing less. How then does restraint apply to the digital world? Well, it doesn’t.

Digital media functions on the currency of excess. Don’t take my word for it. Just look at some of the other browser tabs you’ve possibly got open when reading this and the myriad of embedded ads in a single YouTube video, just begging for a microcosmic slice of your precious fragmented attention. It is becoming increasingly difficult to pull back and focus on any one thing. Because you aren’t meant to.

The cross-platform synchronisation of applications (or ‘Apps’) mean that distractions don’t only distract you. They follow you like a lurking shadow, as you transcend through digital space from the iPad in the living room to the computer screen in the study. The truth is, restraint was never an operational consideration in the design of the internet. User interfaces of web-pages and other digital media may espouse certain aesthetic qualities of minimalism and restraint but it most certainly doesn’t function with any of the same reservedness.

Journalist and minimalist commentator, Kyla Chayka, acutely observed that minimalist rhetoric (think sleek iPhones and velvety smooth Tesla car interfaces) is often based on a “maximalist assemblage”. These devices are manufactured under a surreptitious infrastructure of resource-heavy servers absorbing copious amounts of electricity and packed factories of overworked workers. These production elements languish in the background as ‘ambient noise’, occasionally surfacing in a report or two but not nearly close to arresting anyones attention.

The absence of restraint also extends to the content we consume.

There is a certain vulgar opulence to how we’re served content at every turn of a click or swipe. It doesn’t stop. It was never meant to stop. I’m not only talking about the quantity of content but also how saturated our minds have become with ideas. I say this with a certain self-conscious reflexivity of course - this very newsletter is content with a myriad of ideas. But the problem transcends any specific platform. ‘Excess’ is a systemic feature of content generation and curation in the digital world.

In a previous essay, I explored the utility of listening in the digital space; that ability to empathise and connect with others before reacting or responding. The saturation of ideas obscures any opportunity for listening. We become too caught up in the cacophony of noise and endless lists of carefully framed prescriptions on who and what to believe. There is no critical distance to reflect.

It is however worth asking what happens if we deliberately tear away the excess; remove ourselves from this mind-numbing chatter?

I believe it leads to a realisation that is simultaneously tragic and beautiful. We come to discover a troubled world wrought with difficulties, discomfort, ambiguity and one that lacks answers. But here is the funny thing. These pockets of disquiet also give rise to magically wondrous instances of clarity - where the world isn’t about finding the right answer or narrative, it simply exists for what it is. No pretensions. No accusations. No scheming. It is there to be savoured and addressed in your own time, at your own pace, without judgement. Because discomfort becomes uncomfortable only when it is pregnant with subjective meaning. Otherwise, it is just like any other word - present or absent, nothing more, nothing less. But how does one develop an equanimous relationship with this flailing world of ups and downs?

For one, it goes beyond having a clean study or an organised sock drawer. It involves possessing a mind that remains open to ideas but is not necessarily invested into any single one. To use the open-tabs browser analogy; you are aware of the multiple attention-vying tabs of content in your browser, but you also have the restraint to engage with what is right in-front of you first. Letting the ideas in your immediate environment percolate and simmer, savouring the presiding unease and awkwardness of not being connected to multiple things all the time.

This stripping away of excess allows one to ravel in their own human presence. There is an element of restraint in not pursing new things, ideas or thoughts. It reminds us of our own resilience in relying on our ‘humanness’ without the protective ‘padded walls’ of distraction. We are arbiters of our own reality and it is time we took control of it rather than allow the media platforms to dictate it on their own terms and conditions.

Restraint is then not just about holding back, but it is really a form of introspection; an aching and persistent call to look within. Digital platforms and modern technology may appear earnest in extolling principles of restraint, from gadgets to measure your screen-time to applications that provide you with a guided meditation experience; all to supposedly limit your media engagement. And in some ways these features do help manage media over-reliance. It diagnoses the problem. However it doesn’t offer a cure. It provides a short-term reprieve not an alternative for a deeper and more self-centred analysis and expression of the human condition.

Georges Perec’s La Disparition (1969) is an ingenious masterpiece but not only because of those missing “e”s. Perec compels us to think what their absence might mean to both the unfolding narrative and to the author in writing around this self-imposed restraint. He was not able to say his own name or use the word ‘parents’ - a fitting reflection on the gravity of identity loss and bereavement. Perec’s literary experiment was no intricate exercise in virtuosity or superficial minimalism, it was an artful lesson in being human through restraint. A lesson we could all use in the digital age.

Something before you leave…

Peter Paul Rubens’s 16th century dramatised painting, Daniel in the Lions’ Den, has been a personal favourite when I think about visualising ‘restraint’. The painting features our Old Testament hero looking longingly to the heavens as nine ferocious lions circle menacingly. Whilst a departure from the original biblical interpretation, I’ve often perceived it as a visualisation of the almost futile human struggle to disengage with a world that ruthlessly and insatiably clamours for every ounce of our attention.

Thanks for your wonderful company this week and as always, I’ll be back next week in your inbox, giving voice to moments of humanness in a curiously digitised world.