When skill obscures art

If you want to be a writer, don’t learn to write

Wait! Just Listen is a free weekly Sunday newsletter on all matters relating to the human condition, best read in the morning with a freshly brewed cup of coffee and a side of raspberry jam biscuits, or a treat of your choosing. As Virginia Woolf once said, “pleasure has no relish unless we share it”, so if you enjoy my written musings please subscribe and share this with friends and family.

Let each man exercise the art he knows.

- Aristophanes

I grew up in a fairly scholastic household, an environment fostered, in part, by the cultural valorisation of formal education in Singapore, the country where I spent most of my formative years as an adolescent. I vividly remember memorising copious amounts of information from textbooks, supplemented with a myriad of one-page compendiums on “how to write an essay”, replete with checkboxes so you could tick each step off as you go. There was a feverish race amongst fellow peers at school to internalise all these steps because it came with the insurance of passing the end-of-term exams.

Writing was then, less about artistic flair and intellectual experimentation, and more about meeting stipulated institutional ‘requirements’ under the watchful tutelage of teachers who were on a one-track mission to get you there. There was a sterile and exhausting quality to learning and writing - one that was very much premised on overcoming academic hurdles.

Fast forward some 25 years later and there is, rather uncannily, a gradual resurgence of bite-sized online courses (both paid and free) on learning to write and a range of other art-oriented subjects. Whilst it is heartening to see so much focus on a craft that has not always been as thoroughly explored in mainstream discourse (writing that is), my childhood pedagogical experiences have, perhaps unfairly, made me sceptical of the actual utility in these otherwise well-intentioned offerings.

You see for me, art and more specifically writing, begins in the dark, never as a finalised vision. The genesis of a good piece of writing always stems from a blank canvas where discovery and learning is progressively communicated in all its incoherence and incompleteness, eventually reaching a crescendo of clarity.

The idea of learning to write, either from a structured curriculum or otherwise, seems painfully odd, much like learning how to think or feel. There are of course core structural nuances that any competent writer should know such as grammar, punctuation and cadence, if poetry is your jam. But beyond these technical intricacies, writing should never be reduced to a skill, because canonising it into a neatly packaged skillset suffocates its artistic merit in favour of someone else’s tried and tested recipe.

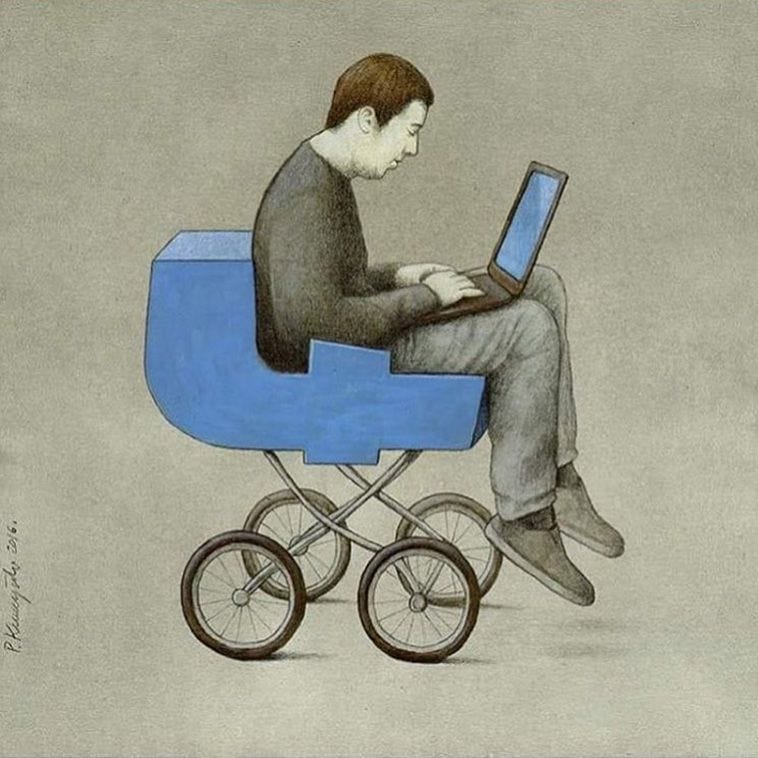

I think it is often forgotten that writing, just like any other art form, allows us to both find and lose ourselves in the process. It implies uncertainty and disorientation, pain and risk. Whilst the Internet has offered us access to some brilliant and sometimes obscure examples of literary masterpieces, it has also unwittingly reinforced an economy for streamlining and simplifying traditional art forms. From music to computer programming, there are guides promising a hassle-free learning experience and a fast track route to mastery; a highway to the boulevard of artistic greatness with the promise of professional validation, all with 4 easy payments.

I don’t have a problem with these resources or its claimed effectiveness in uncovering the supposed undiscovered ‘genius’ residing within us, but I do have an issue with how these guides seem to propose a false equivalence between skill and artistic expression.

For example, one may learn how to play a guitar in 20 days (it took me 10 years to become a proficient player), but translating that acquired knowledge into a self-expressive art form can never be learnt. Sure, it can be mimicked or influenced by the media we consume, but inherently, it should showcase a defining quality, no matter how subtle or bland. Which brings me to my next point.

A quick survey of recent online writing courses and their respective curriculums suggests an intense focus on making content more conspicuous - prose that ‘stand out’, ‘grab attention’ and ‘draw you in’. Whilst these are important tools in a writer’s arsenal, the overt fixation with visibility and self-promotion seems to imply a quiet desperation to arrest audience attention at the cost of actual heartfelt communication. As a result, the intended range of emotions and ideas in art remain obscured or stifled.

Now more then ever, distraction is incentivised and legitimised as the purpose of art over meaningful engagement. This is in part due to the relentless pursuit of artists and creators to grow audiences at any cost (because it pays the bills) leading to the gradual degradation of artistic integrity and truth. In its most vulgar form, this dissolution of truth materialises as click-bait content and dare I say it, online writing courses.

Beyond the marketing speak and superfluous PR frills, an artist is a vehicle of truth, not because he is privy to some objective reality but because he focuses attention upon ideas and facts that provoke intellectual and spiritual consideration. Great writers for example are able to unstitch complex patchworks of reality with surgical like precision, offering a unique insight into the human condition. There is an obligation to uncover an essential truth, regardless of what it is.

But the Internet has somewhat diluted our attention to artistic truth/meaning in favour of branding. From TikTok video trends to snazzy Instagram filters, the delivery and packaging of art takes centre stage and, in some cases, it becomes the ‘art’. Technology is often seen as an instigator of these cultural shifts.

Iris Murdoch — a rare philosopher with a poet’s pen, and one of the most incisive minds of the past century wrote about the ‘tyranny’ of technology in disenfranchising art, under the guise of cultural change.

A technological society, quite automatically and without any malign intent, upsets the artist by taking over and transforming the idea of craft, and by endlessly reproducing objects which are not art objects but sometimes resemble them. Technology steals the artist’s public by inventing sub-artistic forms of entertainment and by offering a great counterinterest and a rival way of grasping the world.

- Iris Murdoch

The end-result is a mainstream focus on the reproduction of artistic form. Further to this, mainstream culture has normalised ‘artistic-handholding’ - where people are guided in creating templated forms of reality in various artistic fields. As such, the courage to be yourself (not a shadow of someone else’s inspiration) and the fearlessness to embrace the uncertain has all but vanished in contemporary artistic pursuits.

The skill of writing and more broadly of producing art, has in certain quarters, become a shorthand way of reproducing learnt and memorised knowledge, devoid of instinct and emotion. But it is not all doom and gloom and the solution to addressing this sacrilegious watering down of artistic expression is disarmingly simple.

It simply requires an acknowledgement that learning a skill may enable artistic creation but it isn’t a substitute for it. So perhaps, at the risk of incurring the wrath of my primary school teachers, the most enduring skill one can learn about writing is not to learn it at all.

"I think it is often forgotten that writing, just like any other art form, allows us to both find and lose ourselves in the process. "

Great line. Much to think about here. Every artist wants an audience but true artists please themselves first. Nothing wrong with wanting to be paid for our work, but you're right; it often leads to an assembly line mentality, where payment is everything and the work suffers.

There are still true artists, however, and for that we have much to celebrate.