A flâneur's notebook

A dive into the world of flâneury against the pandemic stricken backdrop of life.

Welcome to Wait! Just Listen, a weekly series of short essays dedicated to unpacking moments of humanness from the all-consuming web of digitisation. If this type of content enriches your life in any way, please consider subscribing. If you need more reasons to subscribe, then click here. Twitter is my primary method for tracking the cultural and creative pulse of various ideas, so feel free to get in touch (@trippingwords) if you have a topic or theme you’d like me to explore.

“For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate observer, it’s an immense pleasure to take up residence in multiplicity, in whatever’s seething, moving, evanescent and infinite: you’re not at home, but you feel at home everywhere, you see everyone, you’re at the center of everything yet you remain hidden from everybody…The amateur of life enters into the crowd as into an immense reservoir of electricity.”

-Charles Baudelaire

The figure of the flâneur—the care-free strolling observer and passionate wanderer, a key trope of nineteenth-century French literary culture—has achieved an exquisite timelessness. The word comes from the seventeenth-century term flânerie (Flâneury) – to stroll or idle without purpose. Flâneury is an intricate exercise for the mind. It invites an immersion in exteriority, over petty individualistic needs. Because only through an eradication of the ego can one observe the textured world around, in all its nuanced glory and gritty reality. The flâneur exhibits a detached and composed sensibility towards observing communities, without necessarily ever being part of it. Ultimately, the flâneur is the unprejudiced collector and connoisseur of cultural detail.

It should be noted that there is an element of idleness associated with the flâneur and with it an assumption that all observations are conducted from a position of relative privilege in which it is not necessary to engage in the daily grind to make a living. This however does not imply an ignorance towards middle-class predicaments. Rather the flâneur benefits from the impartiality of being uninvested in any one specific ideological position or social circumstance/class.

Walter Benjamin ushered the flâneur into modern discourse in 1927 through his Baudelairean inspired cultural analysis titled, ‘Arcades Project’. The flâneur was, under Benjamin’s lens, a figure that was sensitive to the bustle of modern city life, but with enough critical distance to understand the inextricable forces of capitalism upon cultural taste and institutional decision making. In other words, the flâneur served as an amateur detective armed with the important task of unravelling the conditions of modernity, which included class tensions and the social stresses of urban life.

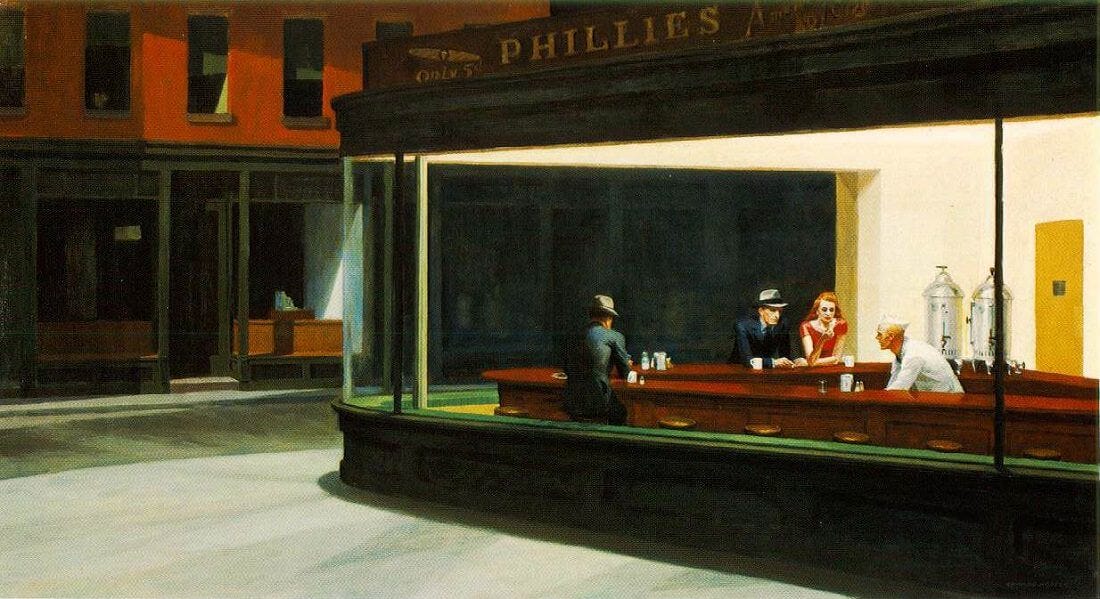

The pandemic has coerced many to examine the overlooked textures of everyday life. But perhaps most evidently it has sharpened our sensitivity to displacement. Empty train stations, deserted city centres and eerily calm highways have constituted at least part of how we’ve universally experienced the disorienting effects of mandated lockdowns.

Spaces that we’ve frequented have acquired a new emotional valence. There is an off-kilter energy that pervades these spaces - an impersonal blank canvas that once housed a multitude of conversations, memories, ideas and gatherings. A special kind of silence reverberates. One that paradoxically captures the essence of human behaviour in human absence.

Flâneuring for a day

I had an unorthodox induction into the world of flâneuring during my first trip into an empty office, post-lockdown. As I expected, the humdrum of everyday office life seemed a distant memory from the moment I walked through the building’s front glass sliding doors.

Littered throughout the office space were various signifiers of the mad rush that ensued when people were first told to work from home, back in March of 2020. Half-eaten mouldy sandwiches, haphazardly placed chairs, unwashed dishes and coffee mugs in the kitchenette. Each object painted a uniquely individual narrative and further highlighted how daily routines were broken. My return seemed more akin to an archeological expedition, piecing together bits and pieces from the ‘rubble’ to make sense of these scattered realities.

On my travel home that day, liminal places such as stairwells, roads, ally-ways and corridors seemed to carry an eerie surreality. These places have traditionally served as a means to an end - to proceed through (quickly) but not linger in. Except, their relative emptiness seemed like less of an exception when the entire city was enveloped in a similar sense of vast barrenness.

The absence of human presence compels us to transpose our own assembled thoughts and memories onto these settings. In some cases, we make sense of it all by tapping into a long-buried memory of how these places looked, sounded and smelt like pre-pandemic. Amidst the emptiness we, rather ironically, find ourselves mapping our surroundings and evoking its living qualities.

The cafe across from my place of work, a somewhat comforting fixture of my morning coffee drinking ritual for the past 6 years, has closed indefinitely. All that’s left is a hand-drawn picture of a sad emoji curiously taped on the front door, perhaps a reflection of resignation rather than indignation from the former owners. It serves as a grim reminder of the treacherous economic implications that lockdowns have had on small-to-medium businesses. For the casual passer-by and patron like myself, the cafe’s closure had brought to the fore memories of the countless trivial and meaningful conversations I’ve had with colleagues during quick lunchtime coffee escapades.

In the supermarket adjacent to the cafe in question, large perspex shields have been put up on all check-out counters. There was a sign upfront emblazoned with the words: “Please keep a safe 1.5 metre distance when paying” - a reminder of how simple transactional actions are now also bounded by perimeters and thresholds.

But things are gradually changing.

As various communities and nations delicately creep out of their imposed lockdowns, flâneury has assumed a revised meaning, in my mind at least.

The pandemic weary flâneur is more acutely aware of the complexity of the world in a layered sense. Every space, setting and social scenario carries with it a heightened sense of measured caution as (most) people deal with physical distancing guidelines, Covid-paraphernalia (e.g. masks) and new crowd density limits. There is also a lingering and overarching sense of (sometimes visible) unease over the possibility of future community outbreaks, an occurrence that could potentially plunder all into the lonesome abyss of another lockdown.

The art of people-observation, especially in urban city settings, now more than ever, requisites a study of real-time social and spatial negotiation - how people navigate through the quotidian rigours of life both in their movement and interactions.

Every hand-rail, petrol-pump handle, lamppost, train-strap, carries with it a ramified density of immediate history. Who might have used it before? Did the said person have vague sniffle or a stifled cough? Were basic hygiene protocols being adhered to? Was the surface adequately sterilised?

These concerns may prove to be overblown when one considers the science (formite transmission is still relatively rare) but they exist as part of a larger spectrum of casual anxieties that come with leaving the house.

Social gatherings and meet-ups in public are similarly less frivolous and more inhibited - people tend to meet for a finite time with a specific plan, at least in my experience. In most cases, if you are meeting someone for the first time post-lockdown, a fleeting moment of mutual unease pervades as realisation dawns that many social niceties, once taken for granted, are now reduced to a head nod, a smile and a wave. Skin-to-skin contact poses a risk many are simply not willing to take (for now at least). Although on occasion, one would see the odd and clumsy fist-pump.

From the point-of-view of the flâneur in a pandemic riddled world, social and cultural observation isn’t about, as Baudelaire once exclaimed, "reap(ing) aesthetic meaning from the spectacle of the teeming crowds”. In fact one could argue that there is a greater element of profundity in flâneury now because of how absence and emptiness, two central motifs in recent public life, confer their own significance, not just on immediate reality but on an immediate historical past.

No longer is the flâneur a man or woman of the crowd or an unassuming bystander soaking up the sun in the hustle and bustle of life. They are now deep excavators of meaning beyond the visible and tangible, ploughing through past memories and experiences, to re-live and re-vision the present. Part of this renewed form of investigation into reality involves a form of scavenging amongst new and old signifiers (whatever they may be) to resurrect meaning. Their curiosities aren’t just confined to understanding what is, but in what was and what might be.

In current times of uncertainty and relative change, the flâneur’s footsteps and peripatetic practices pave the way forward for a more sensual grasp of reality.