Objectivity is widely regarded as a cornerstone of responsible journalism and research. In more recent times, it has also been an area (read: minefield) that academics and scientists have surreptitiously side-stepped from acknowledging, as referring to it meant drawing attention to the possibility of bias - akin to committing analytical blasphemy. In my field of data science and analytics, objectivity isn’t as vehemently debated (as far as I know) in a field widely perceived to embrace the quintessential virtues of accuracy (think angels with innocent faces). For example, we quite often subject our work to robust and iterative data triangulation tests - the practice of using multiple sources of data or multiple approaches to analysing data to enhance the credibility of a study with the objective of reproducing identical outcomes/outputs. The ability to provide quantitative forecasts, reviews and predictions with considerable and convincing exactitude is part and parcel of the job.

However there remains a niggling problem that not many feel comfortable acknowledging - nothing (no entity) is truly objective, and we need to start being openly frank about it. All accounts of truth and objectivity have varying degrees of inevitable imprecision and doubt, no matter how small, negligible or indistinct. Even the most technically astute data-driven algorithmic workflows require human judgement when it comes to applying specific insights in broader organisational and corporate settings. Perhaps most evidently data can become a tool to (sometimes falsely) justify preconceived ideals, ideas and intuitions through specific frames of interpretation. The idea that an elusive universal truth remains mythically embedded within copious reams of data seems laughable but yet it remains a constructed truism in the ongoing data-driven revolution.

Don’t get me wrong. Data is an invaluable asset to decision-making but its core utility has been somewhat expanded in recent times. Citizen scientists, have now become mainstream - members of the public with a strong affinity to data science and its processes now have the ability to publish specific observations on publicly available evidence/data sets. While the democratisation of the field is certainly positive, it functions on the presumption that all of society have at least a baseline level of data literacy to navigate complex new informational waters. That presumption isn’t always true. The underlying concern here however isn’t about the democratisation of data science but more broadly it is the unquestionable devotion and faith applied to data-related entities and the idea that some ‘objective truth’ is accessible if one is armed with data. In other words, the sanctity of data is revered at all or any cost.

Nora Bateson in her essay, Reckless, provides a poignant reflection of how data and its associated narratives communicate a degree of objectivity by the sheer virtue of its existence as ‘fact’.

“Huge scoops of numbers get formed into patterns that are totally decontextualised, and then, good heavens, and then we call it information…The thing about numbers is that they pretend to be ‘objective’, they carry a tone of ‘facts and figures’, when they are objectifying and are much more slippery in the stories they carry than poetry.”

- Nora Bateson in Small Arcs of Larger Circles

In the rest of this mini-commentary piece, I’d like to briefly tease out a few key accounts of objectivity by academics and philosophers and then provide my own views.

Objectivity and its various (intellectual) shades

The operational (‘layman’ if you like) definition of objectivity stems from the premise that personal feelings and opinions obscure, dilute and trivialise facts and evidence-based content. Media, seen as the last bastions of public voice and institutional accountability pride themselves on maintaining a degree of objectivity in their reporting. The field of research (across the sciences and the arts) have similarly aspired towards achieving various levels of objectivity. Even if they have stopped short of explicitly articulating how objectivity functions in specific contexts of their work, there is an appearance of commitment to a ‘broader truth’ so as to faithfully represent ‘what is’ rather than ‘what should be’ or ‘what could be’. Inherent in these definitions is an unspoken epistemological consensus of how various concepts, objects and perspectives are arranged and situated in the world. But as several scholars and philosophers have pointed out, the objective truth is never cut and dry. Rather, it precariously rests between the realm of subjective experience and perceived empirical observation, reflecting a changing mosaic of various shifting qualities.

According to Kant’s transcendental idealism, an independent world exists (das ding-an-sich), but we have zero knowledge of it; we know only of the way this world appears as far as the limits of our intelligence and thinking capacity allows. However, Kant asserts that this conceived experience of objective reality will be the same for all humans, because that is part of the human condition. Put simply, every object has an experience.

Putnam defines objective truth as an internal attempt at building narratives of coherence between our different theories/ways of seeing and our experiences. He continues to argue that it makes no sense to talk about objects independently outside of that dialectic. For example, the word ‘computer’ still refers to ‘computer’, but computers are not an independent, intrinsic property of the world; they are part of our classificatory schemes, among others.

Bruno Latour in his much publicised work on actor-network-theory, established a position in which all entities in the world (humans, objects, ideas, theories, etc.) are seen as ontological hybrids1 that move around, connecting and reconnecting in a network. It is these movements that determine the notion of objective existence and nonexistence. An interesting account that really speaks to the internationality of different contexts and ideas that we are surrounded with.

Hanson (1958) famously stressed that “People, not their eyes, see. Cameras, and eye-balls, are blind” (p. 6). Hanson draws attention to the gestalt switch figures that can be seen as two different things but not at the same time. The central question for Hanson was really if something different is seen each time, or if it is a different interpretation of what is observed? Hanson subscribes to the view that our observations are always affected by our subjective perceptions and innate theories.

Feyerabend went (a mile and a half) further in that direction and claimed that objectivity is subjective. The difference we make between an objective and subjective opinion, is according to him, a pragmatic distinction to differentiate between individually authored accounts/ideas (e.g. democratic ideals or what financial independence means) and what he calls ‘protocol statements’ - observations articulated as ‘fact’ based on what we believe to have ‘factual’ qualities. In other words, Feyerabend refutes the notion that there is a semantic difference between objectivity and subjectivity and that the only difference lies in how we classify sets of ideas to serve a specific function, whatever it may be.

So what is objectivity? No…really.

I believe objectivity is a question rather than an assertion or a descriptor. It is a point of inquiry into how various contexts co-exist, connect, overlap, conflict and confront each other. So take for example the idea of ‘objective journalism’ - what does it actually mean? No journalistic piece is objective in the traditional sense of the word. But if we approach objectivity as part of a larger question - we open up room for understanding how the author stitches various contexts into a seemingly whole reality.

The stitching may be rough and uneven, there may be holes, there may be extra thread and jagged edges, but it is objective in so far that it attempts to tell a cohesive narrative, or present a semblance of one.

The above analogy would apply to even the most cold forms of scientific data - where there is an interpretation to be made, we are in actual fact attempting to answer the ‘objectivity question’ - how do we piece together a coherent narrative based on the contexts that we have access and are privy too from our analytical vantage point. Given such an approach, we are actively refraining from imbuing data with a significance that it truly isn’t qualified to possess in the first place. Data isn’t the elixir of truth. It is a stitched representation of reality - perhaps with perceivably neater seams.

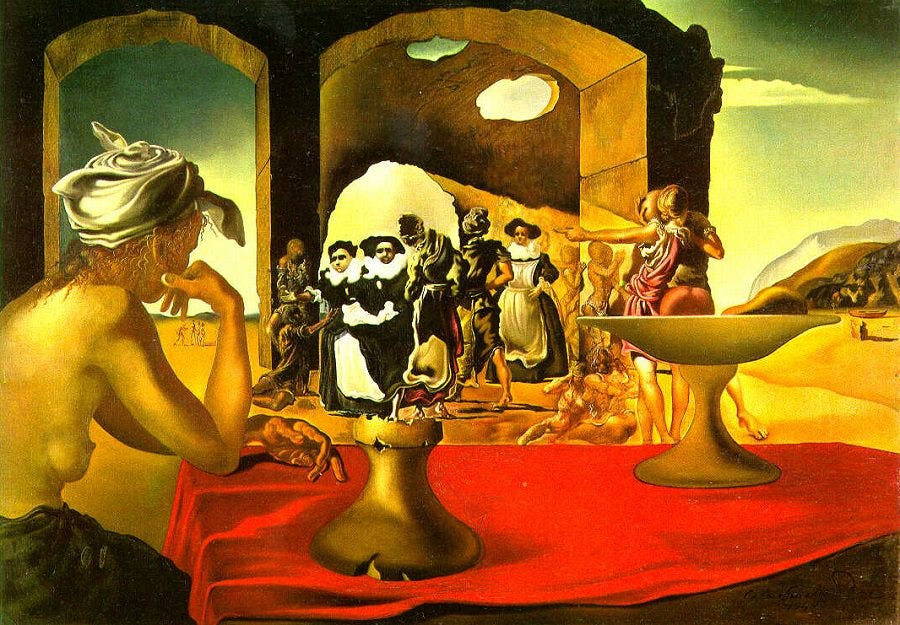

I also think the central value of approaching objectivity as a question rather than an assertion or criteria is how it invites a sense of social empathy. We are invited not to instinctively cast a judgemental eye on a supposedly ‘objective’ piece of work (regardless of what it is - perhaps a photoshopped image of a celebrity?) because truth isn’t a foregone conclusion or expectation. Listed below are some broader positive implications that approaching objectivity as a question brings with it:

We know it is not an objective entity no matter what the creator/analyst claims there is no sacred and intrinsic ‘truth quality’

We are compelled to investigate further into the various contexts behind its assemblage because there isn’t an expectation for a central truth

We have an underlying social responsibility to listen and relate to the entity in question because there is no truth value we can lean on to fully understand what is being said

Notice my deliberate use of the word’ assemblage’ rather than ‘assembly’- assembly is a set of pieces that work together in unison as a mechanism or device while assemblage is a collection of things which have been gathered together or assembled. There is no fixed device or mechanism in question here but rather an electric mix of sometimes strange and sometimes ordinary perceptions and narratives, interwoven and cobbled together into a perceived wholeness that is represented as being an objective semblance of reality.

Objectivity may be an imperfect, overused, painfully cliched and politicised term but it remains a valuable point of reference for further inquiry.

The idea that an entity is entirely made up of the different relationships it has with other contexts/entities.