Welcome to Wait! Just Listen, a weekly series of short essays dedicated to unpacking moments of humanness from the all-consuming web of digitisation. If this type of content enriches your life in any way, please consider subscribing. If you need more reasons to subscribe, then click here.

But before we get started on today’s topic, I’ve a favour to ask. If you get a spare second, please consider sharing these weekly scribbles with someone who might enjoy them just as much as you have. Your continued support has made this literary voyage supremely rewarding.

“‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty’, – that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

- John Keats

As I write this from my home office, there is a house ant navigating, what it would perceivably see as, a series of monstrously humongous obstacles on my desk; the computer keyboard, a set of speakers, my Apple AirPods and a worn leather wallet. It courageously and somewhat resiliently overcomes each obstacle, climbing up swiftly, pausing for a second, as if to marvel at its own efficiency, then charging forward to the next hurdle without a hint of hesitation. It is on a mission - most likely one that involves access into the packet of sugar coated raspberry biscuits tucked in the corner. Either way, I can’t help but marvel at how mother nature has showered this little creature with a level of hardy doggedness one would normally associate with a ravenous lion.

There is something implicitly beautiful and splendorous in how contrasts play out in the world with varying outcomes. The weaving together of varying qualities, experiences, shapes and sizes amidst the humdrum of everyday life is truly intriguing.

But this essay isn’t about the trials and tribulation of the common ant, or at least not specifically. I want to talk about beauty. Let’s start with a light dose of history that has shaped how I’ve often thought about the philosophical origins of beauty and its relationship to aesthetics, at least in the (English-speaking) part of the Western hemisphere.

The Aesthetic Movement of 1860-1900 was a period in the nineteenth century when a group of artists, architects and designers sought to define a new ‘beauty’. The intent was to create art that freed itself from the shackles of establishment ideas and increasingly archaic notions of morality. There was a growing sentiment that Art should thrive on its own merit, and embrace a narrative that uniquely underlines its existence.

Beauty was valorised as the purpose of art, its raison d'être. This included ravelling in a reality freed from moral or doctrinal constrains. Any scholar of late 19th century English history would be well versed with famous advocates of the artistic movement, such as Walter Peter and Oscar Wilde, who explored non-confirmative living, pushing against standards and protocols - creatively questioning the limits of what is socially acceptable.

But for me, the Aesthetic Movement was crucial because it formalised a concerted and systematic questioning of beauty, as a quality that deserved independent interrogation. I’m less concerned with how beauty was defined during the period than how its main premise was challenged.

Fast forward to current times and that spirit of interrogative questioning - of what beauty means - has somewhat paled in significance, at least in mainstream culture. Most modern day reflections on it tend to revolve around specific niche issues such as body-image or the fine arts without ever addressing the more general question of what beauty means in the first place from an ontological perspective.

There is an almost cringe-worthy vibe in asking how beauty is conceived in modern art. Nobody ever does that anymore. It is irrelevant, they say, because beauty is everywhere. But that’s a textbook way of avoiding a potentially difficult question. It subscribes to the mentality that there is no value in questioning what is omnipresent. But yet we showcase every hackneyed conception of beauty we can think of at every opportunity on social media.

Instagram (yes, that gridded social platform millennials seem so fond of) for example, is now home to a very formulaic form of ‘art’ - toned bodies, lavish lifestyles and mildly-irritating dance routine videos (says the middle-aged soul in me) - all deftly packaged into bite-sized squares of consumer idealism, feeding our ravenous appetite for sensory engagement, with every scroll or double-tap. The main offering of Instagram is predominantly visual; the underlying cultural or social context is rarely the main feature as the images capitalise and saturate our perception, before the rest our brain cells can catch up. This is not a criticism of the platform. It is just the way things are.

The point I want to convey is that beyond manifest beauty (what is observable), there is an electrifying sparkle to questioning beauty itself.

What does beauty comprise of and what are the common assumptions attached to its quality? How does it work and what does it make us feel? These questions force us to take a momentary step back to simply marvel at the natural laws that govern how we live, love, learn and die.

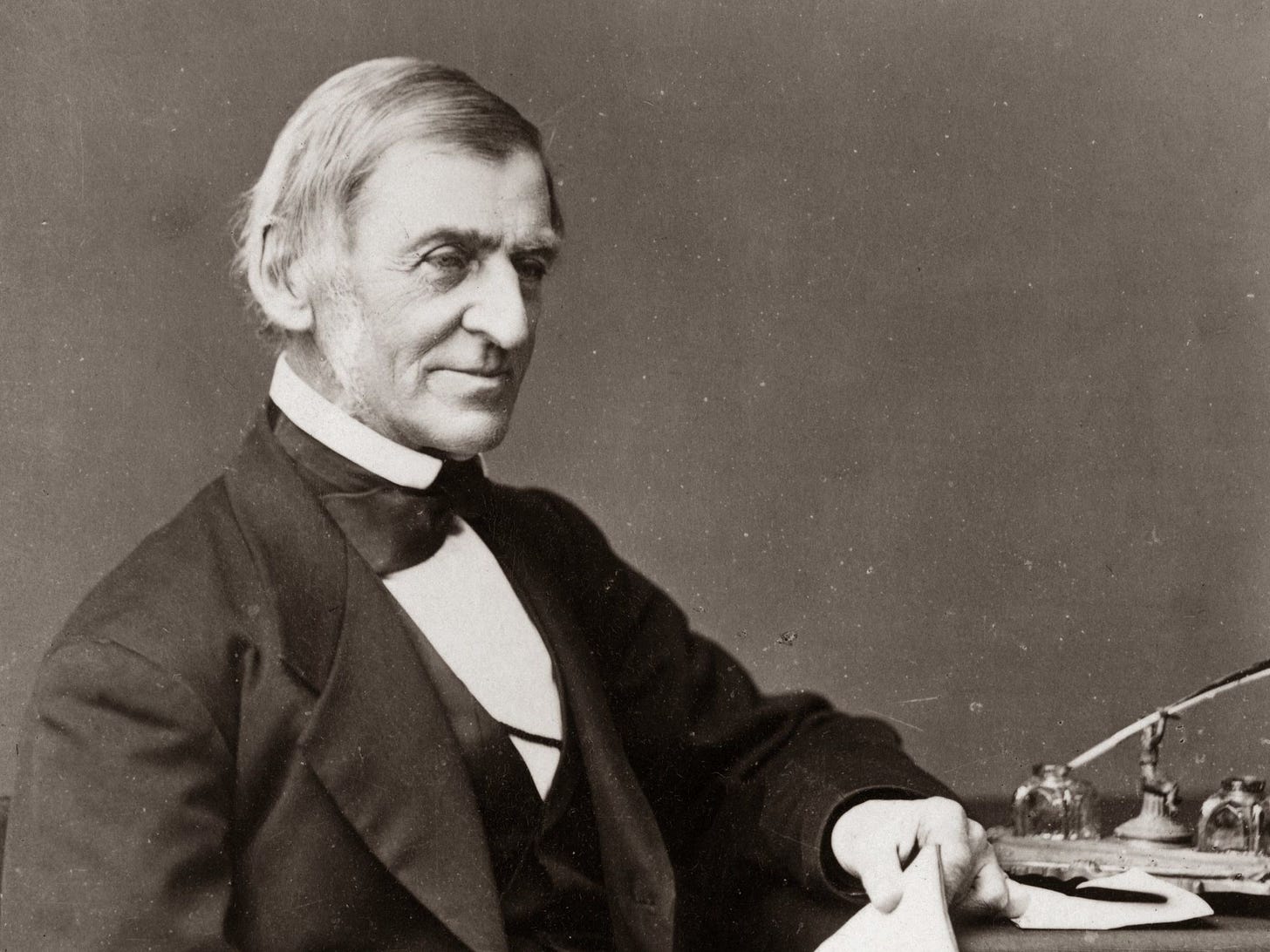

This approach was famously adopted by Ralph Waldo Emerson who quite poetically uncovered that the value of beauty lies in the questioning of it.

“The question of Beauty takes us out of surfaces, to thinking of the foundations of things. Goethe said, “The beautiful is a manifestation of secret laws of Nature, which, but for this appearance, had been forever concealed from us.” And the working of this deep instinct makes all the excitement — much of it superficial and absurd enough — about works of art, which leads armies of vain travellers every year to Italy, Greece, and Egypt. Every man values every acquisition he makes in the science of beauty, above his possessions. The most useful man in the most useful world, so long as only commodity was served, would remain unsatisfied. But, as fast as he sees beauty, life acquires a very high value” - Emerson, Essays and Lectures

Beauty for Emerson remain embedded natural laws which influence the basic order and function of things and beings in the world.

It rests on necessities; such as how our diaphragm expands and contracts to cause our lungs to fill with air and then empty out again. Or how baby elephants suck their trunk for comfort just as how human babies suck their thumbs. Or how a warbler migrates over hundreds of miles of land and ocean to sing in the same tree.

Seen in this way, beauty is understated and yet brutally efficient or what Michelangelo (the artist, not the mutant turtle) would call, “purgation of superfluities”. There is an almost rhythmic fluency in how the laws of nature work which such mesmerising exactitude, to affect our experience of reality. Just as how our pulse beats periodically as confirmation of life, the laws of nature majestically orchestrate the hidden symphonies behind our existence.

Beauty then isn’t something one objectifies nor is it a static quality to behold. It starts the moment one has a dynamic dialogue with the intellect - that presence of mind to absorb the world and its myriad of eccentricities with calm and detached curiosity. It is this ineffable aspect of beauty that remains obscured in the noise of self-indulgent consumption.

Whether it’s the thought-provoking brush strokes on an original Vincent van Gogh painting or the adventures of an isolated household ant, beauty is most enchanting in its rawest and untouched state when the laws of nature are so evident and yet so obscure. Now that is beautiful.

interesting read and substack! check me out if liking themes such 'identity https://tumbleweedwords.substack.com/p/episode_004-identity