The curiousness of small talk

A Derridean take on small talk and friendship and its relevance in the digital world

Welcome to Wait! Just Listen, a weekly series of short essays dedicated to unpacking moments of humanness from the all-consuming web of digitisation. If this type of content tickles your fancy or any other part of your intellectual self, please consider subscribing. Also, a warm welcome to the influx of new subscribers (and a few notable literary luminaries!) who have joined us on this voyage. I’m truly humbled.

I attended my youngest son’s kindergarten parent-child catch up at a local playground last weekend. It was a social event for parents and children. If you know me, then you’d also know that the thought of fraternising with total strangers in a noisy kids playground isn’t top on my list of life’s priorities. But as most parents can attest, parenthood involves accustoming one’s self to doing things that are, to put it mildly, somewhat uncomfortable, because, well, we do it for the kids.

Upon arrival at the playground, I was quick to spot a few dads fidgeting and waiting for someone to break the ice, whilst their partners were busy in conversation, pencilling in future playdates for the upcoming Easter holidays.

You see the thing is, I hate small talk. Hate it. And what I really mean is I'm abysmal at it. But at this particular event, the silence was palpable and the meek efforts by others at breaking the silence ranged from sporadic throat clearing to straight out sighs of boredom. An intervention was needed, and needed fast.

“How’s it going?” I ask a presumably mid 30-something old father leaning awkwardly on a lamppost, whilst his wife continues her animated conversation with another mum. “How’s your day been?”

He replies, looking relieved and grateful for the silence-breaker, “Ah, not too bad. What are you up to?”

I reply with equal relief, “Not much. Just spending time with the family”

At this point I realise that small talk has zero semantic value. No meaning whatsoever. Zilch. Nada. Instead it prioritises social function. It showcases the ritualistic quality of language; the communication of ideas or information is secondary, almost incidental. The speech is mainly meant to serve the purpose of social bonding. It asks and answers familiar questions and dwells of topics of reliable comity and mutual comfort.

Often at events like the above, I’m reminded of a passage from a little known novel I read in my late teens by the Indian author Anurag Mathur titled, “The Inscrutable Americans,”. In the book’s opening, the scion of a hair-oil empire, Gopal, embarks on a trip to the U.S. for a university education. When an immigration officer at the J.F.K. airport asks, “How is it going?” Gopal, oblivious to the wonders of small talk and its pervasiveness in Western culture, replies the only way he knows:

I am telling him fully and frankly about all problems and hopes, even though you may feel that as American he may be too selfish to bother about decline in price of hair oil in Jajau town. But, brother, he is listening very quietly with eyes on me for ten minutes and then we are having friendly talk about nuts and he is wanting me to go.

The passage above and my ‘scarring’ experience at the playground both unravel an interesting aspect of social norms and friendship. They are contrived and there is nothing at all seemingly natural about it. I may be unfairly overgeneralising here and over-personalising this very unscientific hypothesis, but I’ll tell you why in a bit.

First, I’d like to bring your attention to a quote that I’m sure you’ve come across if you, like me, have dabbled with philosophy at any stage of your education.

“O my friends, there is no friend”

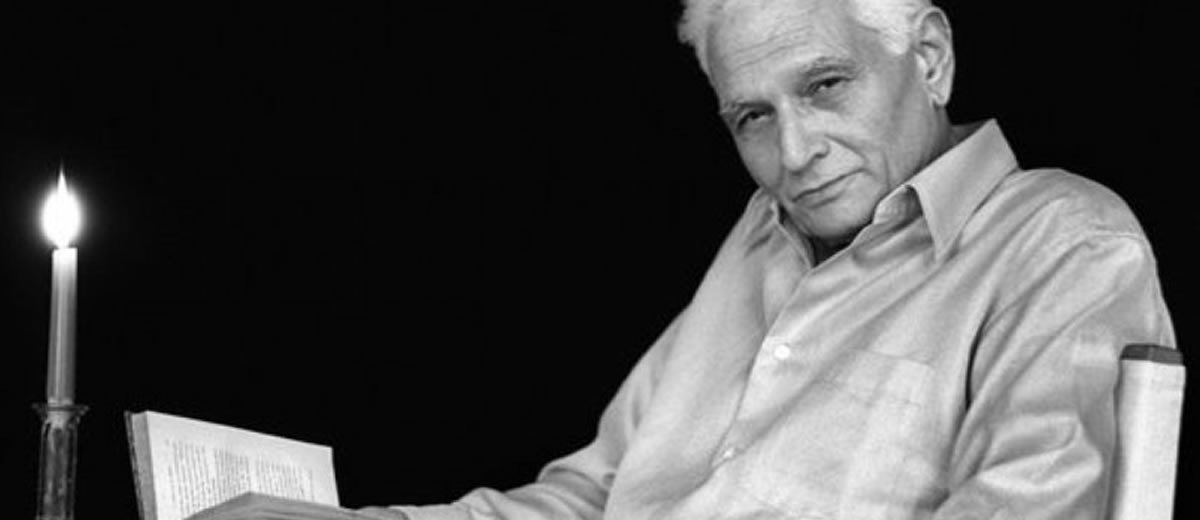

The above aphorism is used by Jacques Derrida1 as a motif for each of the ten chapters of his book, Politics of Friendship. It is a deep text. I’ll admit Derrida's obscurantist prose isn’t for everyone. But beyond its hair-pulling complexity, the book has a disarmingly simple premise; the function and possibility of friendship isn’t a truism but one that needs to be confronted, prodded and unsettled. In other words, friendship doesn’t exist in isolation as a coherent concept. I strongly resonate with that assertion.

One of the cornerstones of Derrida’s argument is his grappling with the differences between love and friendship. On this point, Derrida follows Nietzsche in querying whether friendship might be “more loving than love”.

Traditionally friendship is considered to involve reciprocity, constancy and commitment, but Derrida questions whether true friendship also subscribes to the importance of separateness, distance, boundaries and caution. There is a hesitancy to the notion of friendship - a gnawing sense that there are two sides to this conceptual coin.

Derrida’s focus on disrupting accustomed understandings of friendship brings forth broader questions on the denial of permanence. There is an ephemeral and transient quality to friendship and socialisation, despite our culturally indoctrinated understandings.

Perhaps the digital world of communication isn’t too far off the Derridean conception of friendship. What we typically seek online is that fleeting dopamine hit; a fizzy zap of connection with someone (possibly in a different location) that’s there for a moment and then absent.

This interplay with impermanence and continuity, presence and absence, forms the crux of how we define online communication. There is a lack of novelty if, for example, your favourite YouTube channel was live 24/7 or if TikTok allowed 1 hour video snippets instead of its snappy 60-second time limit. There is a hidden joy to its brevity and succinctness. Such applications specialise in curating the moment. It provides a regular flow of bite-sized content aimed at providing a series of quick-fire dollops of audience satisfaction.

Big tech companies have long realised the monetising potential of the ephemeral and impermanent nature of communication. People may idealise their intimate online connections or rich digital-only friendship communities but the truth is, its pleasure is largely derived from a state of ephemerality. It’s that ever unreachable carrot at the end of the stick that keeps us logging back on for more.

Small talk then feels unnatural because in many ways it imposes a mirage of permanency; I’d have to remain engaged for an unknown finite amount of time. There is no mystery (apart from meeting a new person), no immediate end I can tangibly initiate unless I wanted to come across as a jerk. The conversation will flow (or stop) when it does. That quick dopamine hit is more inaccessible than say logging on to Facebook messenger for a quick chat. One has greater control over the flow of time in online setting. It is harder to end a conversation in-person than it is to end one online. At least in my experience.

Online platforms such as Twitter and Instagram acknowledge the fact that friendship is ultimately voluntary and vague, a relationship that effortlessly slides into the background of life. Almost like ambient noise. You connect with some and you resent others or remain apathetic. There isn’t a definitive protocol to follow. The flow of socialisation is largely arbitrary and somewhat random.

Interestingly, and something Derrida has covered quite a bit in his books, is that friendship only makes sense when viewed in contrast to other anti-social elements in our lives; enemies, online trolls, or troublemakers of the general variety. The ‘ignore’ or ‘block’ feature, now part of so many social media environments further highlights the contrast between communicating with someone that offends and one that doesn’t.

“The possibility, the meaning and the phenomenon of friendship would never appear unless the figure of the enemy had already called them up in advance, had indeed put to them the question or the objection of the friend, a wounding question, a question of wound,” Derrida writes. “No friend without the possibility of wound.” As with all binaries in life, one half contains the seed of the other and no single half tells the full story.

My reflections on Derrida have led me to conclude that for some, friendship is perceived as enduring; for others, it’s a sporadic fleeting moment of intimacy catching up on years lost. There are people we only talk to about serious matters, others who we only relate to in the merriment of drunken nights. But underlying these natural predispositions is the often understated realisation that friendship and socialisation aren’t concrete concepts. They exist in relation to everything else in life. And as such, their impact on our lives are subject to fluctuations and change.

Friendships can complete and complicate you. Energise or weaken your resolve. There isn’t ever a single effect or affect. It affords a mixed bag of experiences. Perhaps then, social media with all its algorithmic trickery, has uncovered a fundamental truth on the Derridean notion of friendship.

Underneath that mask of heavy intellectual pontification, I wonder if Derrida was ever a maestro at playground small talk. I could use a friend on that front.

Derrida is here quoting Montaigne whose essay entitled ‘On Friendship’ was first published in 1580. Montaigne attributed this saying to Aristotle although the original quotation has not been located in Aristotle’s work.

An easy to read concept of friendship dealt with extensively both in terms of depth and breadth, but with succinctness. It was a mind awakening read. Thank you for this article.