So you’ve launched a new product or service and the reviews are flying in. Some people are complimentary, some brutally honest and others seemingly caught up in a miasma of indecision. In all my years of speaking and writing about data analysis and consumer research methodology, I’ve come to realise that people are generally (and sometimes unhealthily) obsessed about two things: how positive or negative a review is and customer ratings (i.e. number of golden stars). While these indicators are perhaps the most explicit tools for assessing the immediate viability of your business, they only scratch the surface and a very tiny part of it at that. The thing is, the value of your business isn’t predicated on these metrics.

The true value of your offering is embedded in the contexts that underline these reviews - the messy and sometimes unexplainable interconnecting narratives and associations that people form about your product with various other aspects in their equally complex and messy lives. If you prefer a more scientific and empirically astute definition, contexts are a frame that surrounds a focal event (i.e. a product or service in this instance) and provides resources for its appropriate interpretation. UX researchers have over the last decade developed finely tuned ways of exploring context, with a specific emphasis on user experience (See diagram).

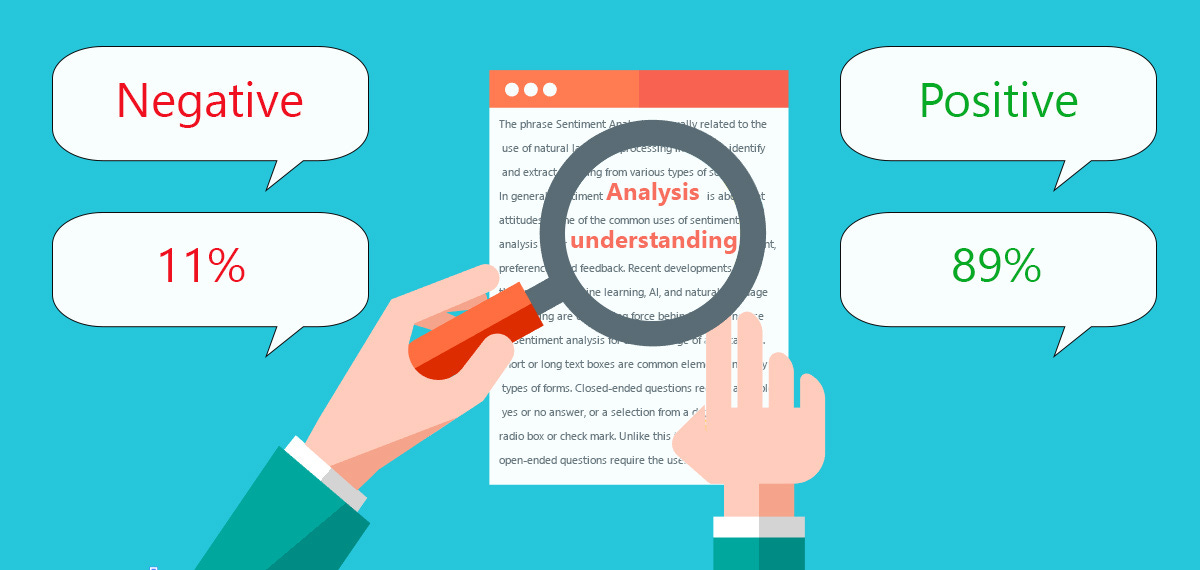

It is worth noting that the sentiment-analysis applications used to determine and categorise specific contexts (i.e. positive, negative and neutral) are typically based on an unsupervised lexicon-based approaches. This means that unsupervised techniques are utilised for predicting the sentiment by using knowledge-bases, ontologies, databases, and lexicons. Each are equipped with detailed information, specially curated and prepared just for sentiment analysis. This ‘contextual information’ is in most circumstances largely supported by rigorously researched presuppositions of the words/phrases an average person could use to express various states of emotion.

In the case of analysing product reviews, we would ideally like to throw our analytical net wider (than our UX counterparts) to capture the more abstract cultural and social nuances that are central to how people use specific products and services. These ‘shades of grey’ areas, as granular as they may be, are integral in understanding how your business/venture delivers against very specific social and cultural arrangements in everyday life. Knowing how your product ‘works’ with everyday life rituals, in spaces and places typically obscured from the primary scope of your offering is essential. Because no idea, service or ‘thing’ is ever created to be utilised in a vacuum.

Listed below are a few pertinent examples of what to look out for when analysing something as amorphous and fluid like context.

Consumer lifestyle, life-situation & life-stage

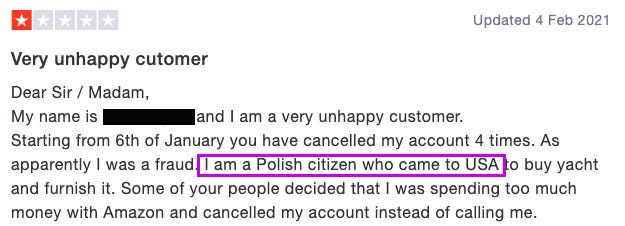

Reviews offer insightful information on the demographic, living arrangements, lifestyle and life-stage of your clients/customers. People often find a product or service inconvenient or exceptionally brilliant in relation to the product’s broader impact in their everyday life. These products are usually incorporated within the intricate and sometimes layered context of life. There are important insights on an individual’s lifestyle, life-situation and life-stage that can be gleaned from certain reviews, which is invaluable (and free) consumer information that can be utilised for further refining your product and/or service. Take the following examples of reviews from Amazon’s website as an illustration of the point above:

Product value goes beyond product use

The value of a product or service offering germinates from its first public announcement or appearance not just at the moment of use. There is an ambience and set of emotions attached to every product or service including the user interactions it may foster before any tangible transaction occurs. Brands of marquee fragrances have for decades masterfully exploited this fact by marketing their products as part of an entire envisioned lifestyle - an investment into a perceived experience that is culturally unique and aspirational. Consumer reviews do at times make reference to these broader dimensions of perceived product value, references that are crucially important for your in-house marketing and branding gurus to be aware of.

Here are some examples of the aforementioned point, extracted from various Google reviews. Both these excerpts are part of 5-star reviews and nested within a larger body of text that wouldn’t necessarily be apparent upon a quick read. Interestingly, both these excerpts were also completely missed by 3 sentiment-analysis AI software1 platforms programmed to differentiate between negative and positive reviews through text analysis.

…the blue packaging made me think of winter. I don’t want to be reminded of winter when I use sunscreen.. it looks a bit too much like something I’d use when feeling cold or maybe when going for a mountain track! I don’t know. Just feels that way… - Review on Sunscreen

No complaints. Wallet is seamlessly manufactured. Nothing low-rent about this. Also wanted to say that the tartan background on the website upon purchase really provided a warm-feeling of the highlands - nice little nod there to history… - Review on a men’s wallet

People can love and hate the same product or service

Sentiment analysis tools use natural language processing, text analysis, computational linguistics, and biometrics to systematically identify/categorise and quantify affective states and subjective information. These tools will map the distribution of consumer sentiment around your product or service. The challenge however lies when people have conflicting emotions or reactions - which ultimately resists any fixed algorithmic categorisation.

The reality is, human emotions are contradictory and are entangled with a myriad of ideas and perceptions. Any attempt at siphoning out a single ‘happy’ or ‘sad’ reaction to a product is, to an extent, imposing a form of bias which may not necessarily exist in the data. It is in essence a reductive methodology that constrains rather than develops the generation of rich consumer-driven data insights. Take for example a car purchaser’s review of a new Audi RS3 he just procured.

It’s a car I want to love and one I feel mostly positive about. The interior is sublime and that raucous 5-cylinder engine is music to my ears. But there’s a link I’d like to see - I feel that I’m being driven as opposed to the one driving it. The plushness of the steering is positive but only that…I’m wanting more. - Review, Audi RS3 owner

The above review was categorised as ‘positive’ in 2 of the 3 sentiment-analysis text mining programs that were utilised for this case study. The use of the words ‘positive’, ‘sublime’ and ‘plushness’ were decisive in convincing the algorithm that this review was a gleaming example of a satisfied customer. The final text mining software returned a ‘null’ output indicating that there was indeed an ’issue’ with attributing a singular categorisation (i.e. positive or negative) for the snippet of text above.

Ultimately, the review unearthed a perceived fundamental flaw with a sporty car meant for driving enthusiasts - there was an absence of driver engagement and connection, leaving a rather dull but efficient motoring experience (not my view, so Audi fans can calm down).

While cars are typically products that attract a considerable number of robust reviews and commentary pieces from the media (hence making user reviews less revelatory), the underlying principal remains - conflicting reactions to a particular product are not the exception. Taking into account these middle-ground emotive positions (that sneakily avoid algorithmic detection) within the data is a crucial aspect of refining ones business strategy, research and development and quality management. For a small-to-medium enterprise, it could make a difference between a good or great product. Nuance matters, no matter how messy it may be.

Silence is golden but not in the way you think

I’ve sat down with enough product vendors, entrepreneurs and creators to know that unspoken words are just as crucially important than spoken ones when it comes to user and industry reviews and even peer assessments. The challenge however is that most text-mining software specialise on what is present in the manifest content. Its purpose is to paint you a picture of what is being said rather than what is left out or strategically negated. It is a worthwhile exercise to account for specific variables, characteristics, ideas that remain curiously absent in user accounts/reviews. We live in a complex world of ever evolving systems and change - a world with multiple truths, perceptions and realities. It would be high extraordinary if some of that ambiguity (and absence) didn’t seep its way into the feedback we receive.

These ‘silences’ matter in a practical sense. Perhaps there is an aspect of your product or offering that needs further clarification or maybe users aren’t acknowledging a specific feature of your service because it is either (a) taken for granted and hence not ‘novel’ enough to comment on or (b) quite simply irrelevant or superfluous. Either way, it is time we had a systematic methodology for researching, embracing and integrating ‘absence’ into our overall framework/scope of analysis. Uncertainty and absence is a legitimate source of data and information in itself.

Should I shun all automated sentiment analysis platforms?

Yes. Burn them. Throw away the ashes and sanitise your hands immediately for their vile poisonous nature can cause immense psychological affliction. I’m kidding.

There are appropriate instances where the thematic mapping overall user sentiment is useful. They are somewhat scientific and precise enough to provide you with an accessible snapshot of the sentiments (i.e. positive, negative or neutral) your clients/customers gravitate towards.

However, I prefer to see them as reporting mechanisms (more like ‘pulse checkers” for data) rather than true excavators for growth. If you want to unravel and dig out the social and cultural intricacies that surround how people use a product and service, a more in-depth research framework is required. Contrary to what you may think, these frameworks are not difficult to develop. They are process driven and…shock and horror…they do involve algorithms. But that is for a future instalment.

I have deliberately avoided referencing the names of these applications because my point doesn’t concern any specific software but more generally in regard to the limitations of large-scale automated data processing.