The madman deserves a voice

The social masks we wear provide a sense of control over what we reveal. But underneath that constructed facade lies a madman, with an impassioned plea for liberation.

Welcome to Wait! Just Listen, a weekly series of short essays dedicated to unpacking moments of humanness from the all-consuming web of digitisation. If this type of content enriches your life in any way, please consider subscribing. If you need more reasons to subscribe, then click here.

But before we get started on today’s topic, I’ve a favour to ask. If you get a spare second, please consider sharing these weekly scribbles with someone who might enjoy them just as much as you have. Your continued support has made this literary voyage supremely rewarding.

“…thus i became a madman

And I have found both freedom of loneliness and the safety from being understood, for those who understand us enslave something in us”

- Kahlil Gibran

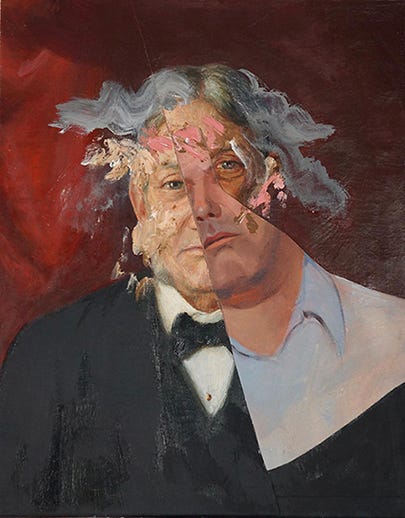

We hold on tightly to our intricately crafted masks, justifying their use as if it were part of a well honed ritual to lead an assuredly meaningful and fulfilling life. There seems to be an unspoken anxiety that should these masks ever slip off, our participation in reality, our ambitions and our dreams will cascade into a torrent of nothingness. The masks complete us, we believe. They imbue a form of comforting subjectivity. They accentuate what needs to be seen. They conceal what is sacred to only our deepest inner conscience - a type of madness that only we are privy to.

But yet there is an argument to make that life is only lived and experienced unmasked.

There is a certain freedom in embracing ones’ madness - the unrestrained and unflinchingly honest version of ourselves that we try so hard to obscure. Because a madman’s perception of reality is often brutally unforgiving and yet hauntingly sincere. In such a context, our perceptions of reality are laid out in all its gritty detail without any compulsion to be apologetic for its brashness or bashful for its lack of ambition. In many ways, the madman shuns expectation, standards and etiquette, and devours his present circumstance, because he answers to nobody but his own prevailing conscience.

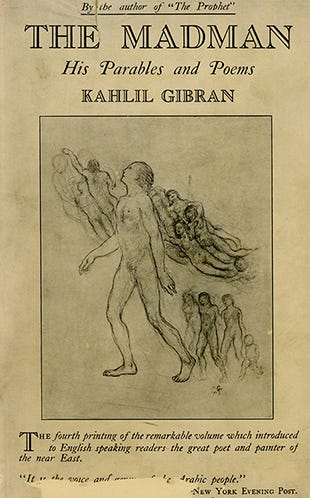

Khalil Gibran, the much revered Lebanese author and poet wrote “The Madman” in 1918. It featured a series of short parables on the absurdity and hypocrisy of our self-righteousness, including our desire to hide our true selves and its perceived unfavourable qualities in fear of succumbing to societal judgement.

As I read his work, I was, on multiple occasions, rendered a starry-eyed spectator, in awe of Gibran’s masterful orchestration of beautiful literary symphonies that resonate long after they end. You see, Gibran doesn’t just narrate the human condition, he paints it so honestly that you soon discover a certain universality to all your fears, longings and vulnerabilities.

Gibran’s main premise, to me at least, seemed to be that madness is in fact the content of our inner most thoughts that remain shrouded in obscurity because they resist typical social categorisations. If I were to drastically translate the above into today’s socially mediated lingua franca; ‘madness’ is the part of your life that won’t ever grace the pages of your Facebook or Instagram accounts because they disrupt self-defined notions of what it means to live a desirable life. Embedded in these social platforms, like all forms of mass media, is an almost obsessive negotiation/interplay between the attainable and un-attainable and our desire to somehow sit in-between. Being polarising or controversial in ones’ views isn’t any more or less authentic, because often these contrarian opinions are manufactured to elicit audience engagement under the guise of authenticity. Leveraging the idea of the genuine self without necessarily being genuine certainly isn’t what Gibran meant by ‘madness’. It is just another one of the various ‘masks’ at our disposal.

We, as presumably high functioning social creatures, are in many ways masters of deception. Through our numerous public facing roles, we painstakingly etch out carefully constructed silhouettes of who we are, always leaving room for mystery and interpretation. The masks certainly aid the cause as they present a specific vision of ones’ self and tantalise with what remains hidden from prying eyes.

Gibran, in a series of mesmerising and almost confessional passages written some 100 years ago, manages to shed light on our unexplainable compulsion to seek out representations of presumed idyllic perfection rather than ravel in what simply is. This is beautifully captured in what seems to be the most quoted prose in the entire book:

You ask me how I became a madman. It happened thus: One day, long before many gods were born, I woke from a deep sleep and found all my masks were stolen,—the seven masks I have fashioned and worn in seven lives,—I ran maskless through the crowded streets shouting, “Thieves, thieves, the cursed thieves.”

Men and women laughed at me and some ran to their houses in fear of me.

And when I reached the market place, a youth standing on a house-top cried, “He is a madman.” I looked up to behold him; the sun kissed my own naked face for the first time. For the first time the sun kissed my own naked face and my soul was inflamed with love for the sun, and I wanted my masks no more. And as if in a trance I cried, “Blessed, blessed are the thieves who stole my masks.”

Thus I became a madman.

And I have found both freedom and safety in my madness; the freedom of loneliness and the safety from being understood, for those who understand us enslave something in us.

There is a certain enviability and gracefulness to the unhinged mind for it seeks its comfort and solitude simply through its existence in nature - “For the first time the sun kissed my own naked face and my soul was inflamed with love for the sun, and I wanted my masks no more”. Freed from the weighty burden of external judgement and self-imposed expectations, the madman achieves complete independence from the masks that he once considered as a staple fixture of his life - a source of artificial refuge.

Yet, we can’t help feeling betrayed (existentially at least) when our masks show signs of breaking or if what it conceals is somehow unexpectedly decoded. Just ask any politician. In this sense, Gibran’s book serves as an almost private and therapeutic confessional, preparing us for the reality of embracing a much simpler and more direct version of our natural selves - one that remains untainted by the socially-imposed metrics of desirability and pleasure.

As we become increasingly engulfed in a digitally mediated meme-obsessed world that champions numerous depictions of the ‘idealised self’ without any point of arrival, it may be worthwhile, on occasion, to let the incoherent bumbling madman inside, ravel in its incompleteness and imperfection. Because, in a universe defined by impermanence, what is there really to lose?