It took decades for me to cut the cord but I’ve finally done it.

I’ve started 2023 consciously avoiding ‘the news’ and the sensationalist rhetoric it routinely delivers under the thinly veiled mask of objectivity. My only exception is when a news story directly relates to my line of work - where the issues discussed (typically around foreign policy) have tangible implications on specific projects. Either way, there is hubris in thinking that reality could ever be told objectively, furthering our collective delusion of mistaking information for truth and meaning. We’re inundated with information and yet face a worrying scarcity of wisdom.

But beyond the above, the news, in all of its eclectic genres, is horrendously violent.

I’m not referring to the explicit headlines and painful visuals of victims that are emblazoned the front pages of the daily tabloids each time a bomb goes off annihilating blameless lives. I’m not talking about the public outcry that resonates through the deafened ears of failed intelligence and faith in the state’s law and order. Nor the anonymous visages covered with black rags who are photographed outside the courtroom, readied for trial procedures, which may go on for months, maybe even years. I’ve zero interest in the subsequent analytical carnival that proceeds every societal tragedy - one that is spearheaded by commentators who pontificate on how the human mind (typically of the perpetrator) can be so malicious and calculating and yet portray an affluent, composed and erudite exterior. These supposed kaleidoscopic revelations are engineered to provoke rather than engage.

The violence I want to talk about here is far more insidious and implicit, burbling beneath the sleek presentation of daily news bulletins. It is what I like to refer to as ‘structural violence’ - the type of violence that places the power of storytelling in the hands of a system that unproblematically dictates the truth through the logic of commercial profitability and a sense of self-afforded legitimacy. The news seems to exude a bizarre chimerical allure around knowing, somehow insisting that to know is to exist, even if the opposite if often just as true.

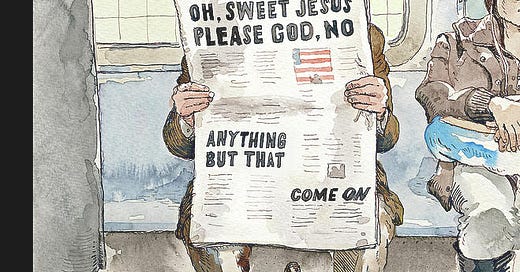

Through its intricate commercial machinery and agenda driven pursuits, the news (commercial media for the most part) is squarely aimed at muddling our understanding of the world rather than enriching it. There seems to be an an almost perverse and unspoken joy in providing information without proper context and interpretation because it is only through this grossly lopsided system of production that the Kafkaesque chaos and drama can unfold - choreographed to pixel perfection in pursuit of clicks, eyeballs and profitability.

This barrage of readily available half-baked information has created an environment where it remains a cardinal social sin to appear uninformed just as it’s enormously embarrassing not to have an opinion on something. Society has, over centuries, developed an inner compulsion to form so-called opinions hastily, based on fragmentary bits of information and superficial impressions rather than true understanding. Because it is more important to appear informed even if the facts don’t quite add up.

And there is nothing more violent than a misinformed and reactive public working on assumptions that are not representations of reality but imaginative figments of it, setting forth moral standards, passing judgement and cementing baseless preconceptions. Walter Benjamin called it a century ago - “Every glance at a newspaper demonstrates that it has reached a new low, that our picture, not only of the external world but of the moral world as well, overnight has undergone changes which were never thought possible”.

It is my belief that sincere storytelling is the only way to mitigate this violence; to cultivate true wisdom in an age of information bombardment. A good story invites a form of transcendence - the reader is encouraged to not only understand the current issues dominating our global landscape but to instigate thinking on how the world should work at its highest moral potentiality. Stories, non-fiction or otherwise, should always helps us interpret information, guide us into integrating that information with our existing knowledge frameworks and finally transmute that into a form of timeless wisdom. The labour of interpretation should ideally rest equally on the shoulders of both the storyteller and the audience.

Rather than have a loaded gun of misinformed narratives ritualistically impressed upon our permeable minds, let us, in the words of Emerson, accept that ‘knowledge is knowing that we cannot know’. Perhaps only then could we begin to envisage an end to this brutal violence, a glimpse of heaven behind all this hell.

It’s interesting once you start pulling your attention way how different the world can look, but also how you start to see the influence of daily news on people you talk with. Really appreciate this week’s essay! This is something I think about constantly.

Yea. So accurate. Been unplugged for many years. I had too many things to do to buy into the narratives. Too depressing. Now to find out it was contrived with set talking points to be set in an echo chamber around the world. Diabolical. Thanks for well thought out word craft. Kudos.